Here be some words of the journey:

Preface:

Beginning with my life and what I wanted to do, or rather what I asked that I could do,

would be a good place to start if this were just my story, but my story is one that wants, (and has

been asked) to be a part of a larger, partially unknown and distant story.

This is a common theme in storyteling, telling my own story as a way to hear a larger story. At first my

struggle was just to begin, to see, to hear, to comprehend in some way what was before me. This

turned into a common theme also- to keep those questions, “what is next?” “what am I doing

here?”, “what or where is the meaning in what I see?” before me. The beginning can be the most

powerful part. Time and again I was reminded to keep the basic questions, the first questions before

me, not to go blazing past them, grabbing the answers as if they were the goal.

At first this was all secret, I told no one, and found out later- that there were few to tell

anyway. I found out how hard it was to tell the truth- to say what it was I wanted, or rather what

was shown, offered for me to do, to take part in. The offer was simple- simple and vast: to experience

the trade routes, the connections, between each area, in California, Nevada, the west,

and… the whole country, the whole continent, and later, even to see the connections between the

continents.

Trade routes- the paths between towns, between cultures. The surplus and sometimes the

rare products of humanity and nature. Focus upon the word “paths”, as in “paths between

towns”. These are generally the shortest or easiest routes, but not necessarily. The route may go

around danger, which may not always be apparent- like a seasonal danger, such as hurricane or

avalanche, flash flood or unfriendly neighbors. These paths may be obvious to the first time visitor,

or they may take an experienced local years to remember and follow correctly. The scope and

detail of just this one word, “paths” is infinite and ever changing, but this is something interesting

to me to learn, to experience, and these paths are given to us all, not just to me, they are part

of the Earth itself, the waters, the sea, the mountains, the plains, the desert and even the snow

covered lands with their frozen lakes; all these areas have their special ways to get across, to get

through, to travel from one town to the next. Of course now there are roads everywhere, but

these roads follow, exactly sometimes, the very trails and footpaths of the centuries before cars.

Interstate 5 in California, Hwy 395, Hwy 14, Hwy 1, all follow old trails. Sometimes the road or

even established trail does not find the way across the mountain, the river, or valley to the next

town or area of interest. The route is then found “cross-country”. All places are connected, one

way or another and discovering these connections is a great joy.

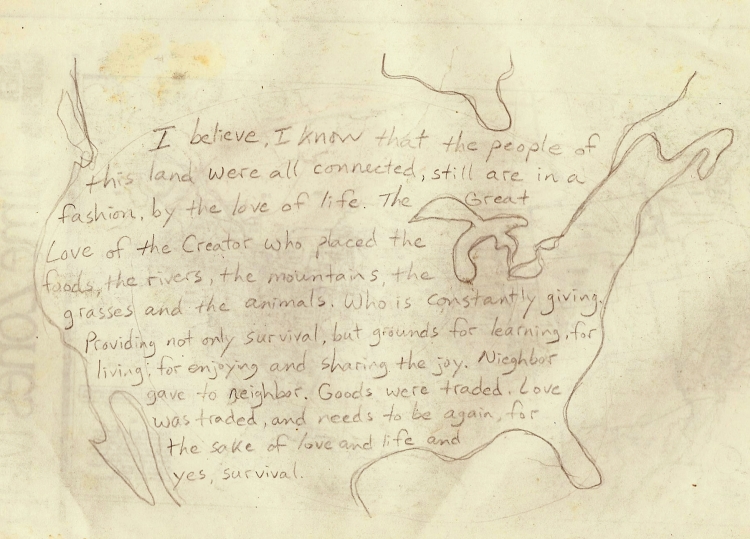

Focus upon the word “culture” and you will discover God, or not. All the world’s cultures

were and are a way of remembering God’s blessings, the Earth’s blessings, and the history of the

people who came before us. The paths connect towns and also connect cultures to each other.

Each area is unique, individual, and each is connected one to the other. This is the whole, the unknown.

The whole of the country is on a much larger scale than the individual person can grasp,

yet as an individual, I can cross through and travel the entire country, touch each area, experience

a whole range of people, places and culture, but to see it all at once, to be everywhere at the same

time experiencing the whole people the whole land, whole sea, all at once and continuously- this

I do not do, I can see and experience one segment at a time. Later I may remember the series or

the accumulation of experiences, I may make connections between peoples and places and cultures,

but to experience all of it- this is on a scale beyond human, beyond individual human capabilities.

As much as we can imagine all at once, we can still imagine more that we are missing,

private conversations, ceremonies, memories that only families and generations of families could

recall, and although everything may be similar across the country as far as human experiences

go, they are still not the same. The whole contains everything, even that which has not yet been

imagined; but grand scale is reflected on a smaller, more human scale within each individual person,

a scale which can be grasped, can be experienced. “Paths between towns and cultures.”

Focus

upon the word, “products”, as in “products of humanity and nature”. The real goods, the raw

materials of nature, the fruits the flowers- our food stuffs and even more important, our ornamentation.

Although more than mere ornament, but the very symbol of beauty itself, the prized possession,

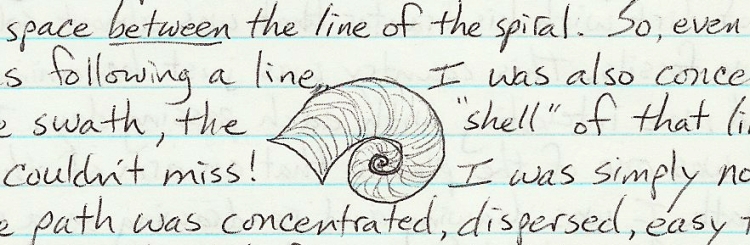

the centerpiece; of what is it made? Shell? Stone? No matter the material, what is important

is the rare and exquisite beauty which shines with a life of it’s own; but then the material becomes

even more important and one must know; of what is this made? who was the artist?

The story deepens as it is told of the expensive, the rare, and the unavailable materials

that once existed, but now, no more. The dentillium shells that are no more, even the abalone,

rare and rarer. Used to be sold in restaurants, no more. The taste, the quality- it became expensive

and then… unattainable, unavailable. What was once common can now no longer be found, the

tale of the old people who still remember, who still have memory of things in their hands that we

never even see- this is richness, wealth beyond telling. And yet there is something even more

valuable still, and this is the knowledge that spirit never dies. These “things”, these clamshells,

trees, buffalo, and people, they have more than their physical existence. The physical may be

rich, but the spirit is beyond counting, everlasting so in this trade network, this whole economy

of life and everlasting life, there is a durability that goes beyond the exploitation, the extermination,

the extinction of species, the loss of forest culture, river knowledge, mountain sheep hunting

techniques; there is a durability that transcends the actual, the beautiful and rich and full. We

think we know what rich is, what beauty lies in the forest or on the mountain peak, we can see it,

describe it, take pictures of it, copy it over and over again until we know that this is beauty, this

is richness, but alas, as much as we can perceive these things, even do these things as drawing,

painting, photographing, carving and sculpting, alas to hold it all, to keep it all, to pass it on, preserve

it for our children, keep these things from wreck and ruin-no, these things we have not

done, but still try to do, for in the trying is the very conscious performance of life itself– the part

we say is sacred, the part we adults take on as our responsibility, as if we could actually pull it

off the sky and keep it, this wonder of life.

Who were these people who carved the stone heads, the gold leopards, the ornate masks

of hard burled wood of oak and hickory? The stone tools, the red paint on the cave walls- who?

Who were they that lived, lived on and on through the ice ages, the floods without paved road,

automobile, electric oven or insulated coveralls. Who had no grocery store, no Sears catalogue,

no navy or army? What did they think? Did they think they could possibly survive all those long

years without steel, glass, or newspaper? One thousand, two thousand, and on and on through the

thousands. Ten, twenty, forty, fifty, where was Christ then? We have had Christ for 2 thousand,

but what of the 50 thousand before that, and the hundred thousand before that?

Do we know how many Christ’s have come, how many times the coming has happened?

Unconditional Love is everlasting, has always been and always will be, and so has this story, this

journey, this job, this life of knowing, acting, surviving, loving, saving, planting, harvesting, cultivating

and building. This is a continual process, one I happen to love, working with the blessings

of the Earth. Running; a story in itself, and so begins a story, a journey, something mine and

yet something owned by no one- this love giving life.

Chapter ONE: Beginnings

Such a beginner I was in 1991, planning to arc northward along the spine of the Sierra

Nevada mountains, such peaceful, gentle mountains, and such a beginner I still am here in 1999,

still feeling new and small after going around seven times.

Starting with a prayer in 1991, and even before that, a love of this country and people;

how could one love this wealth, this richness of interesting fascinating complex intriguing unique

ways of not only surviving, but having fun at the same time? Not only having fun but sincerely

thankful and playful and connected as surely as brother and sister, father and mother. Of course

love, these people are taking care of us, making sure we are fed, clothed, and even more so, they

fill our eyes with beauty, beauty unbelieved and unaccounted for, beauty that saturates and fulfills,

the sounds of the salmon flipping in the river at night, the colors of the water washed rocks,

the feelings of autumn, all these things have time and place and order, they come and go with the

utmost respect and dignity, with regularity and dependability no man could match, but maybe we

can see, learn, appreciate, and take note: look! There is a pattern, a predictable, regular, normal,

forgiving pattern every day of the year, every season, every year and series of years, everyone of

our lifetimes and for every lifetime of the whales and the may flies and the giant redwood trees there

is someone talking, the creator is talking, listen! Love, look! Slowly, carefully, patiently,

courageously, steadily moving, spreading, keeping everything alive.

The sun came up in 1991, it came up a lot, there in Bishop CA. I was there to see it, to

pray in thankfulness for that day, for the sacredness around me in those mountains, those springs

of cold, fresh water and hot, fresh water to soak our bodies in that winter.

The water that heals, Keough Hot Springs, where I met my mother, Pat, who adopted me

at age 30. We had a big family reunion that summer of ‘92, I put up my tipi in the campground,

we ate buffalo meat and sat and talked. Don was even persuaded to smoke his pipe and he was

visited by a black bear who casually looked in to see who was there in the tipi. Having already

covered close to 200 miles on foot that summer, I was lean and strong and very much into enduring

even more, many more, miles of trail in the Sierra Nevada. Forty five days times 20 miles a

day, 900 miles on foot that summer, after 6 years of fire fighting- hotshotting around the country,

itching to get on my own trail, my own time, own pace, eager to see what I was made of for myself,

by myself, with no orders, no one to follow or lead, just the forest and mountain trail. I followed

old trade routes, the passes from east to west and back again… circling and covering

ground, making maps of the mountains and valleys I could actually see and… realizing that even

for such monumental trips as I was taking, the mountains were so much bigger. My maps of what

I actually saw were small glimpses, quick looks at what was, and is, another rich abode of life:

complex, vast, tiny, interconnected, unseen, omnipresent, and so many places, so many places in

those mountains that have been for so many years, eons, knowing themselves, familiar with it

all- each of the hundreds of canyons on each of the dozens of rivers, each unique, each different

in flora, climate, even the fish vary from lake to stream to river canyon, north to south, east to

west it is all huge, vast and complex and it fits into one very compact area of a map of California

which is but one of 50 states in this country which is but a part of the North American continent,

which is only a tiny area of the globe, not even a 1/16th of the total surface, to say nothing of the

depths, or of the worlds beyond, but who can talk of worlds beyond comprehending, beyond understanding;

worlds within worlds. Somehow it is meaningful to us, somehow we are not always

overwhelmed and, to us, we see what we see, know what we know, we live on the scale which is

meaningful for us. There are fish in every lake, every stream, but we fish one lake, catch one or a

few fish and eat them. That is it, on the physical level. On the spiritual level those fish, the ones

that live in our minds, the ones we caught, they live forever in our minds and hearts, that lake, it

becomes a big lake, the lake, our lake, the fish’s lake, and everything the fish eat become important,

the rain becomes important, everything becomes connected. Everything is connected, but

we don’t see that all the time. We see our scale, our level, what is meaningful to us; food,

weather, cold, hot, shelter, transportation, money, clothes, women, men, children, ourselves.

Here is a kernel, you hear stories about people having money, wealth, possessions, power,

but then saying to themselves “what does it all mean?” From this lack of meaningfulness all their

power and money becomes worthless- it has no meaning. With meaning then being a goal- how

do you get meaning? I would say love is meaning, simple appreciation is meaningful, being able

to feel, feel anything at all, and especially the ability to feel good and goodness in things, these

are meaningful, fulfilling experiences. These are experiences that don’t have to end, there is no

end to all that can be loved, learned and cared about. Then there are people who work and spend

their time on things they don’t love in the name of survival, in the name of lifestyle. It takes

courage to change this, to live in the name of love, to seek love, to show your love for the moon,

the stars, the clean air, the fresh waters. To love another person takes courage, to love yourself

takes courage. Where does this courage, that you don’t have, come from? The source, the source

of courage and love itself. From life itself. Life used to be free, now it is very expensive. What is

really living? really doing the survival, the art, the child raising, the celebration, the migration?

Really just being able to sit and survive? To sit and feed oneself, and take care of children?

Two basic things have not been resolved; the requirements of survival, and the requirements

of living, loving, being loved- real meanings in your life. We have resolved these things in

the past; people who survived by certain, specific, religiously set ways. The goal being not to

enslave themselves or other people, but to be free to live and survive. Example: a field is needed

to grow corn and staple crops- for survival, but from the beginning- before the work of survival

is even begun the requirements of living (which includes all life) are considered. Who are we to

say that we need to survive? This question is balanced by asking, and then simultaneously hearing

the answer from Life itself. When you ask this question: “Why do we need to live?- before

the last word is even finished, Life itself answers- “You are given life”- Life creates itself, takes

care of itself, there is no question of deserving, earning or working for life- this is a fact, life is a

given. Survival however is another question- Life or Death, Black and White. You live or you

don’t. In this modern world, everyone sees Death off in the distance, not as part of life, but separate

and distinct from it. In this way, survival loses it’s meaning, “because no matter how long or

how well you live (or poorly), Death is waiting to end all your efforts of survival.” When Death

is seen as being right here, with Life, inseparable, then you can feel, you can know you’re living,

you appreciate how sweet it is, this life, because we have the whole thing, and we don’t have it,

that keeps life fresh, free, unowned and not for sale, unimprisioned, uncontrolled. Uncontrolled

means that when you’re feeling really alive you realize that feeling is fleeting- it’s the feeling

teenagers crave above all else; they despise all else but the feeling of being totally alive and free.

Even if something goes wrong, fails; at least that’s real, not contrived= uncontrolled. Survival

has come to be defined in terms of control, and it’s balancing factor- Life, has been denied, left

out, erased, not cared for, but dearly missed. People who have survived, and lived, simultaneously.

They have balanced the controlled, set ways of survival with the unaccountable, unreasonably

generous ways of the ever-giving Life.

The slow, sometimes grueling, repetitive, obvious and simple ways of everyday life when

added ungrudgingly, when the routine is a joy, a savior even, then the addition becomes

more than the mere sum of days, places and people. Something miraculous, unexpected, uncalled

for happens- a payoff, a chance meeting with just the right person, or a touch of recognition from

the world itself, and suddenly all the work, all the day to day survival and drudgery disappears,

Life appears and is effortless, so much bigger than you ever deserved, but here it is right in front

of you; do you have the skill, the resources, the true kindness within you to treat it right? To

honor and cherish, to remember always this sudden gift which is also obvious, plain, human and

yet so divine, such as yourself? How long will it last? and the answer comes- “Life has always

lasted, has never left, “be patient, Life is going nowhere- but you, where are you going?”

We need not stray away from the ever giving Life, but may live within, and let it live

within us. Nothing is too common, too boring, ordinary, plain, everyday, that Life cannot and

will not walk right in and transform survival into the meaning of Life. Very unaccountable this,

this Life.

OOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOO

There are large periods of time which give me time to think, time to see what is ahead,

and the potential sometimes is so heavy, so full and solid and unmoving- like the potential to participate

in this cleanup, that cause, and another that is so worthwhile, so many just causes, good

fights, so many small people and places being exploited by big entities, and then there are the

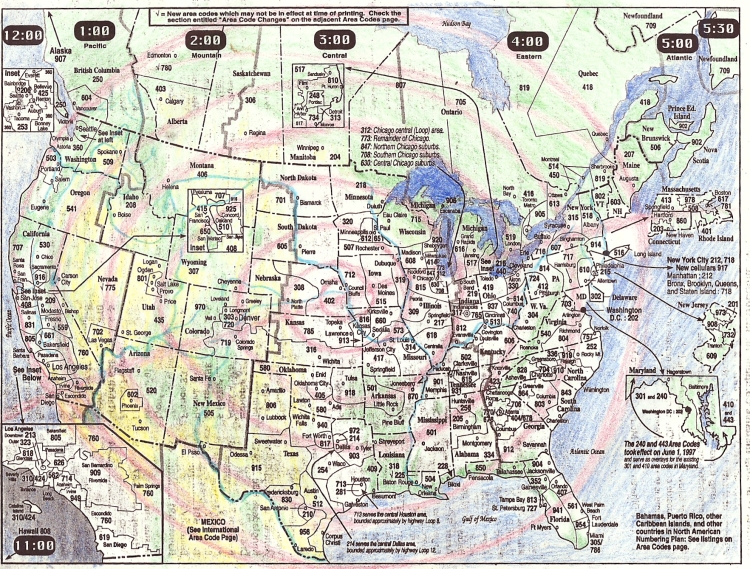

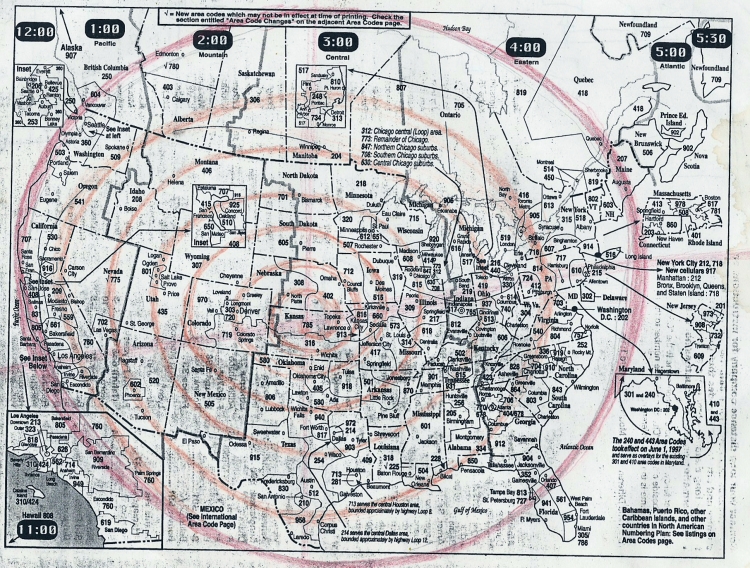

sweeping changes, new area codes added every year, doubled; there are so many people moving

into this country. Many families starting up, all needing the house, the school, the store, the job,

and here I am just sitting, not moving, the summer is over, time to settle down for the winter , time to soak in hot water, eat and sit, watch quail move over the rocks, listen to

birds sing. Sit with immensity of potential and do nothing. This is where action ripens, the winter

of 1991.

Now it is the winter of 1999, November and the heavy scent of roasted turkey is adding

to the building atmosphere of sleep and rest, inactivity and timeless ebb that comes with the winter.

So it’s very easy to remember that winter and almost every winter since 1986, that is when I

started firefighting. The summer’s work was so heavy and full, days seemed like weeks and one

day could put a week’s worth of age on your body. So the winter was a time of collapsing, falling

inward, staying home, visiting, eating and sleeping big sleeps.

Resting and soaking through the winter of ‘91 into the spring when Diane and I stepped

up to the pace, running every day, hiking the mountains around Bishop, CA and visiting with

Ralph, Momma Pat and Nicholas. This is when the prayers for my life and all life

were begun in earnest. I needed, I needed what was here for me to do, the immense potential of it

all and the tiny, individual, specific person of myself. Through the years I worked through the

thoughts and fears of having money, work, a job, a situation- I saw many opportunities, but I

didn’t need many, and this is the step away from security and into the fear; the step toward the

specific, on the spot, the one, the indefinable unknowable one situation, one job, one focus; that

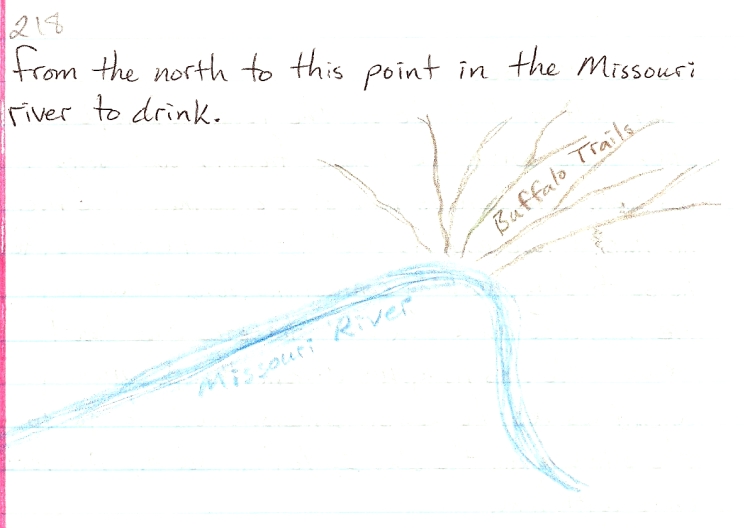

is what I needed. Through prayer, through listening, this is where to start, where I am, so, this

year, this 1992 I begin to take steps to put form, to make a stroke upon the paper, to carve the

block, to enter into the world, a world that has a past, a rich, infinite past whose continuum has

been shattered in one generation, and that shattering took place generations ago, so now one

might say there is nothing left, or one may look and say, “it is all open”, There are also few barriers

to belief, even acting upon belief- this was another fear, but less costly. Acting upon your beliefs

is seldom carried out, fear of what other’s may see you doing, fear that someone will say,

“You there! What are you doing!?” That would actually be nice, it would demonstrate concern or

maybe just acting out of another’s fear of you and your doings, but the horrible reality is much

sadder; the fact is, there isn’t a lot of care for strangers parading around the country, people

would rather not know, too busy to spend another minute thinking about what you might be doing.

Sadly, people may die of neglect more often than being beaten up by bullies for practicing

their beliefs. That wasn’t the case a generation or two ago, but now, neglect, isolation, ignorance

and business inflict more damage than “hate crimes”.

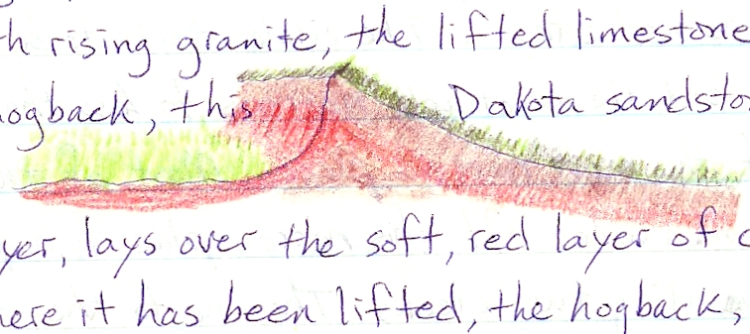

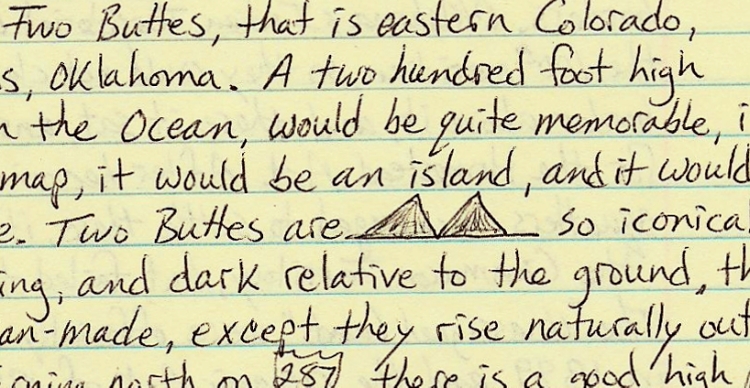

Starting in the southern Sierra Nevada mountains of CA, Lone Pine to Three Rivers and

back, 120 miles by foot trail, and again and again, back and forth, crisscrossing, working my way

northward by going east and west, over the passes, following the old trade routes where pinion

nuts and salt traveled on the backs of generations, through time, for so long that even the recent

break of 200 years is just a momentary, sad, pause. As I did this through the summer I was faced

with two powerful thoughts and feelings. The first; this is absurd, the trade routes are gone, foot

travel is obsolete, and no one, not even the majority of Indians know or even care about trade

routes over the mountains. The second; this is ancient, the ancestors know and care, even when

one person remembers, this is meaningful. And then there are the encouraging feedback signs like

the group in Yosemite who re-trace on foot the old trail to Mono Lake, bringing acorns and

salt to trade for pine nuts, to dance and celebrate mid-summer at the tops of the mountains just

like their ancestors did not so long ago.

So I go on, knowing what it looks like to the outside, and also knowing what is feeling

right on the inside.

After a summer full of hiking on my feet, carrying my food on my back 20 miles a day,

living simply on extended unemployment benefits from firefighting, resting in my tipi and soaking

often in the hot springs, after a summer full of eye filling wonder at the gentle, hospitable

land above the land- (the Sierra Nevada mountain wildernesses), after a summer and fall season

of progress on foot, progress of mind, connection to land and people, past and present, after sustaining

momentum, gathering and recording information , I am ready to rest again, but the momentum, circumstance and

opportunity give me a fling up to Seattle, WA for Thanksgiving. After more prayer and ceremony,

consultation with elders and deeply, deeply asking and simultaneously listening and simultaneously

responding to the immediacy of survival, the next step is seen, shown and presented

for my acceptance. Bend, OR.

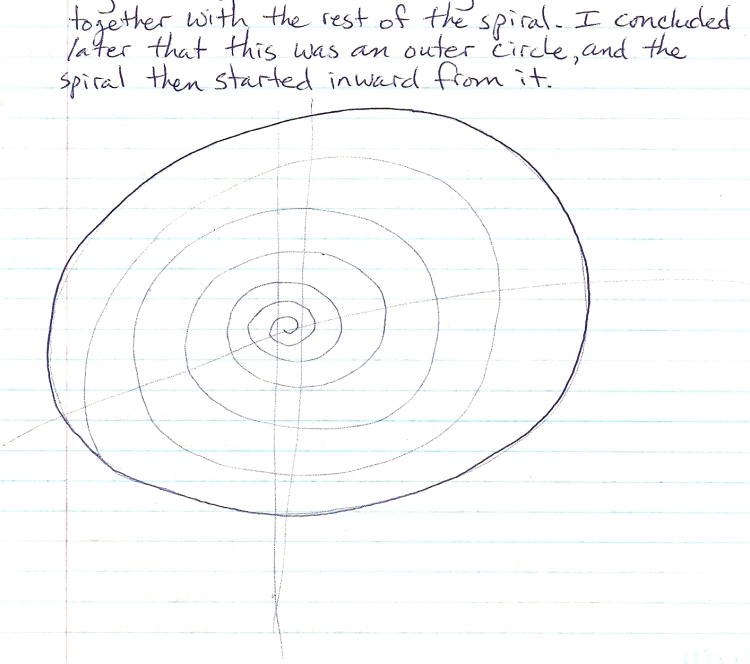

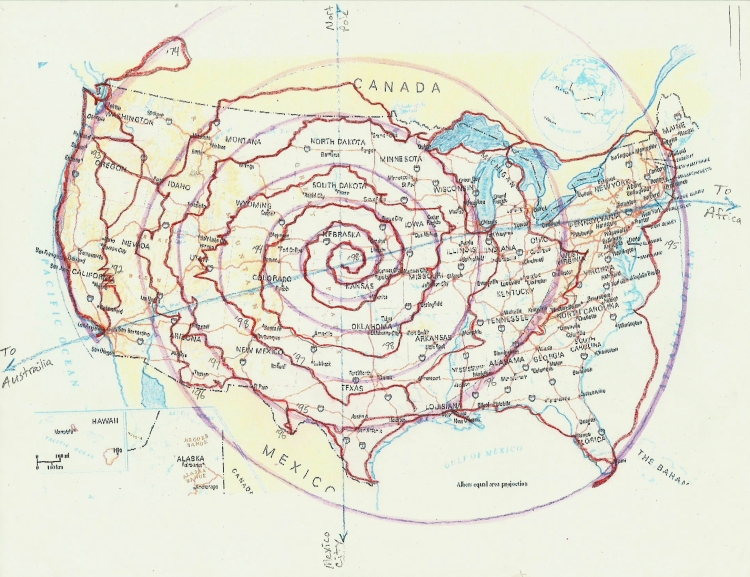

And many more steps beyond- the whole picture, the spiral

path around and through and into the country and more.

Days of study, meditation, hours of

praying with maps, tracing routes with my fingers, seeing with my mind, just as Cherry Gap

stood out on the map 2 years before I actually stepped out of the car (as a crewman for four years, stationed in Grant Grove as a hotshot firefighter) and walked along the wonderful

spot, Cherry Gap, an open vista above the giant redwood forest in Sequoia Park. While a crewman on a fire engine in the

southern Sequoia forest, nearly a hundred miles away I saw, I studied, the map, the map saw me

and told me where to look, where to go, the spot grew warm and inviting to my eyes, there it is

again, where did it go?, there it is! Cherry Gap, Cedar Grove, Triple Divide, Cloud Canyon,

Army Pass, all these places I walked through, around, and down into, as the names grew warm,

as the map foretold, so I went, guided and guide, recorder and recorded by streams, mountain

sides, trees and sky. So I went, so I lived in these places, celebrated and enjoyed them.

I don’t think I enjoyed or appreciated these wonderful places anymore than others of my

time, but the connection to all of them, between disparate places- between the trout lakes, where

the trout fisherman go and the peaks where the mountaineers go and the snowfields where the

backcountry skiers go, the cabins where the rangers stay, the horse trails and short cuts where the

packers go, the inaccessible ravines and defiles where the mountain lion go, the thick, dark, solid

mass of huge tree forest where no trail go, but I go, and appreciate, the trail I appreciate, being

able to move- up, down, over and through the mountains until they become more than a collection

of names, destinations, viewpoints and camps. The whole forest becomes home, like your

house. What would you think of people coming from Nebraska just to see your front lawn and

touch your mailbox? What would you think of people lining up just to get a chance to walk from

your living room to your bathroom, and take photos? Of course they would leave litter and wear

a path into your carpet. They might think your bedroom is prime cow grazing country, so don’t

be surprised to find cow shit in your bed, maybe in your refrigerator too. This is what happens

when the country, the forest becomes your home. Maybe it’s better just to be the tourist, lease the

land, rent it for awhile, or buy and sell it, make a little money. Nothing wrong with that. Unless

you want everything. Unless you want to live and want all the animals and plants to live and the

water and air to be fresh and clean.

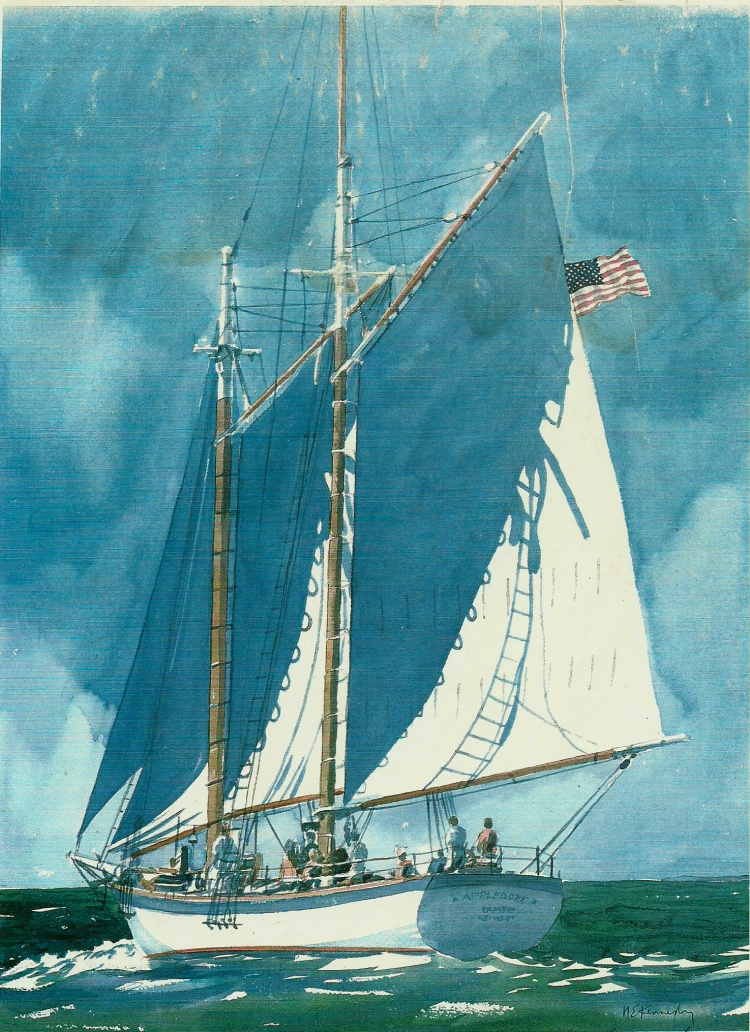

As a boy I grew up going to Catalina Island, by sailboat, before I could walk we would

go. Swimming is big, a big part of our lives, but we live mostly on land, focus upon the land,

take the land for granted and ignore the ocean. The oceans; pacific, Atlantic, Gulf of Mexico and

California are just as much a part of North America as Canada, Mexico and the U.S.A. Not to

forget the Bering Sea, Arctic Sea, Hudson Bay and James Bay. These waters are also these countries; so to

travel the North American continent is to travel by sea as well as by land. The waters are actually

easier routes sometimes than the land, as well as being beautiful places in themselves, more than

just barriers, our corridors and rivers are our home just as the land is. The channel island

sound, the Los Angeles River, Ventura River; these waters connect the great mass of land, the

San Gabriel Mountains, to the Pacific Ocean. The waters and the mountains still feel like the safest,

surest paths to travel the country. I avoided the interstates and city paths, not so much out of

fear of somebody doing something to me, but initially out of fear of loss of focus; that the distractions

and randomness of so many people doing their own, different things would pull me,

distort me, delay and interrupt me just as they delay, interrupt and absorb the rivers, sky and land

around them without giving much of a thank you in return. So much of nature is willing to give

itself to the needy. A thank you is the uniting recognition that completes the gift, and lays the

ground for continued help, fulfillment and recognition. A thank you says, “I recognize this gift,

this fulfillment of my need, and I’m grateful.” It’s a humbling position, but also one of strength

and honor, one of respect.

So in 1992 I was avoiding the interstate, the big cities and the “fastest route by car.” In

general I stayed to the mountains, following their spine up into Oregon and Washington. For

Thanksgiving that year, Diane and I went by car to Seattle, we went the “back” way. Her friends

Tracy and James were living there in the Capitol Hill district. So this trip incorporated some of

the feeling for the opportunity I was being given; to travel between the ancient nations of Turtle

Island. The trip up to Seattle was beautiful, we stopped and stayed in Winnemucca, Nevada for

the night. Ate dinner at a Basque restaurant, family style, beef tongue and sheepherder bread,

rich soup and a variety of foods. The first and happy little snowfall of the year, a sign for that

winter to come. We stayed with my old friend Sue in Baker City, Oregon. Going through the

Owahee river country in southeast Oregon was exciting, knowing about this river that started

deep in the Nevada desert and cut it’s way north through one of the least inhabited parts of the

country to the Snake river, just getting to see some of this open country, learning about rivers new

to me, learning that yes, there are raft trips down the Owahee river, a navigable river is good

news. The band, the belt of movement that I was following, described in ancient, pre-human stories,

is a wide, fluctuating path that blends, sometimes neatly, sometimes definitely separated

from, the adjoining path. Every path has its parallel path, the alternate route and the next route to

the south or north, east or west. The whole country is criss-crossed and covered with trails; short

and long, wide and narrow, definite and obscure, but these paths that traverse the country, region

to region, spiraling, curving with Earth from North Pole to South, continent to continent, these

paths not marked by trail signs “per se”, although trails and roads and rivers and mountain chains

do coincide with them. These paths are more like ley lines, continuous streams of potential that

not only make the long distance travel easier, they actually encourage and keep people, animals

and other motile life going in certain directions. Sometimes there is a perceived obstacle, a

mountain lays across sideways, an ocean presents itself, or a road-less area the size of Manitoba

and Ontario full of dense forest and huge lakes. These have been obstacles to us, as a civilization,

as a group; there are no cities in these places, but as a consequence of being stopped by these

perceived obstacles, over time more and more people came to this obstacle and stopped, and

there are cities now at the edges of these perceived obstacles. An obstacle for a city, for a group,

a town maybe, but not an obstacle for an individual. Individuals have made the crossing, traversed

the mountain, the ocean, the desert, the road-less forest and great lakes. These obstacles can

be wild, vast, cold, wet, steep, dry, rocky, swampy and road-less, but this usually means the animal

life and hence the food supply, or other natural resource, is abundant. This abundance usually

built if not helped supply the city. Los Angeles in an insertion of one of these lines into the

continent from the ocean, a landing point of people from all over the world, like New York was

earlier, but New York is actually an exit point from the continent into the ocean. Actually there is

still continent underneath both these places in the ocean, so the lines are just following continent

that has been covered by ocean. These lines, these paths and flows of movement are not human

or for human convenience, any more than buffalo, trout, trees or corn is for human convenience.

Some animals and plants are convenient to harvest, just as some ley lines are easy to travel

along. It’s the obstacles, and the human response to them that is interesting . Obstacles to travel

have created boundaries for people all over the world, but these boundaries aren’t set in stone,

even if they are high Rocky Mountains. There is always a pass through the mountains, or a way

around them, and people lived everywhere on this continent, from Death Valley to Denali, Newfoundland

to Baja California, so these obstacles weren’t so much barriers or walls, even the

ocean was traveled upon, even lived upon for months at a time. My point is that trade progressed

and continued across the continent, east to west, north to south and everywhere in between. People

stayed and adapted to their home area, but they knew about, traded with and traveled to their

neighboring areas often. The mountains, oceans, deserts, weren’t so much obstacles as teachers,

educators, a part of the land itself that kept people honest- you had to really know when to go,

what to take with you, where to find how long the journey would take, where to find storm shelter-

for several days or weeks were needed to travel by foot or small boat across these challenging,

beautiful places. People love this time, this time out, away from home, facing the raw spirit

of the land and learning that even here, as everywhere on Earth, there are meals to be had, special

herbs and medicines found no where else, and a special kind of food, a love for the beauty

that hurts it is so big and omnipresent and fleeting and delicate. So this country, this California

with it’s long chain of mountains both inland and on the coast, some of the steepest mountains

anywhere those little coast mountains- 5,000’ feet tall isn’t so big, but five miles from the Ocean!

That is a 1000’ elevation gain every mile. (Wear sturdy hiking shoes). From Mt. Diablo, east of

Oakland, you can see the most square miles of land and sea than from any other mountain. It is

5000’plus in elevation, but the land in every direction around it is flat. A sacred, sacred mountain,

many herbs and medicines there, and now a park, a preserve at the top, along with the radio

and microwave power antennas. Almost every sacred place has been seen as a vantage point, a

developer’s dream, a benchmark, a launch pad for technology. Fortunately most are so remote or

rugged that the old cost/benefit ratio was too heavy on the cost side. Most parks, preserves,

natural and wilderness areas are so today because the economic cost was too high to log, mine,

or otherwise ruin the area.

So what am I doing, going through this motion, moving throughout the country? Well for

one thing I am seeing firsthand, the beauty, the abuse, the neglect, the snow, the air, the people in

every place which is so different than travelling by imagination and vicariously through other’s

stories. I gave my self to God and he gave it back, so I feel like I can do what I want, what I’m

interested in; go where I want to go. Of course I have limitations, these things take time, and

money, and energy. I could only go so far, see so much, spend so many days, so most of the time

I felt like I was getting a quick look, even if I spent all day sitting in the same spot, the sun going

across the sky, me staying in one place, thankful all the while to be able to do this.

It’s easier not to know that to explore the whole country around Bishop, CA by foot

would take several, dedicated lifetimes. It’s easier not to know that this exploration could continue

northward for hundreds of miles along the Cascade chain of mountains into Oregon and

Washington, likewise a parallel exploration along the coastal chain would probably take twice as

long. It’s easier not to know these things, not to know what you’re missing, but this life is not

easy, it is good and hard. The real part I’m missing though is not so much the exploration, but the

years of living in one place along the western slope of the cascades in southern Oregon, along,

say the Rouge River. I saw the Rouge once as a kid, we drove over the bridge at the coast. There

are a thousand such places I would care to spend a lifetime. The spirit of ever-lasting life calms

my fire to do it all, “There is time, an infinite amount of time, you can do everything you want to

do.” Sometimes I get through by saying “sour grapes”, “oh, that place isn’t so great, the people

don’t look that happy, and it would be so much to deal with, especially now days.” Sometimes I

feel like a time traveler from another planet, sometimes I probably look it too!

In my mind, what I would like to do, if I could have things my way, I would like to participate

in a trade system that is ongoing, in progress. A trade system of not only the goods of

Native America, the nuts, rice, acorns, hides, shells and fabric, but the system of culture, the system

of love. These things are not valued solely for their purposes in eating, decoration or utility,

they are loved, just as people are loved. We would no more think of selling the site where turquoise

is dug than selling a mother, a child a brother or sister. And so on with each of our resources;

these are traded, certainly, but more in the sense of shared with neighboring people, just

as our relatives are shared among us, like a child is brought up by everyone, not just the parents,

an elder speaks to the whole community, not just their blood family; so trade, the word trade in

the Indian sense was and still is a win/win situation. Trade helped stabilize, not destabilize communities.

People depended upon their relationship with their home town first, their home economy,

their acorn trees, their salmon creeks, their hunting mountain. Having a good relationship at

home is first and foremost. When each community is strong and well fed in this way, then trade

can commence, trade is a way of sharing surplus and acquiring special, well loved foods, tools,

songs, dances, ideas, marriage partners, memories and joy. This is the way it was done, people

knew how to live, how to take care of themselves and their neighbors. A full and rich life, not

free of sadness and pain, but certainly not just sadness and pain, certainly well balanced by the

whole range of life experiences, with one wonderful and glad blessing- no one group of people was

out to destroy, to totally wipe out, another group. This was not possible, not necessary and certainly

not a desired condition.

All of this has changed, new ideas, new ways of being in the world have been introduced

to this land. A great death, a great sadness was brought to this country. Not knowing how it was,

how people can live on this land; not knowing may be easier, for it is hard to know what one is

missing. It’s hard to know how things ought to be; now they once were, harmonious, sustainable,

for century upon century. But it’s impossible to go on and not know, as is the situation with many

people today who have no memory, no knowledge, no basis, not a clue as to how things can

work; how to base an economy, how to raise children, how to take care of elders, of the ground,

build a house, catch a fish, draw a picture. The really difficult part for people is that think they do

know how to live, after all, they have all the pieces, the education, the house, the spouse, the

kids, the school, the food, the medicine, everything. Everything but one thing, one thing missing,

what is it? The total picture, how “everything” fits together- food, kids, medicine, speech, ideas,

houses, countryside, weather, songs, dances, and dreams. People have sat down and tried to figure

it all out, make budgets, plans, attend meetings, keep the lawn moved, kids fed, plumbing

fixed and do a hell of a job at work. And maybe they can and do keep it all together and fit everything

together- for themselves. But can they do it for everyone else in town? No. Everyone else

has to do it too. We all have to do it, figure it out, follow through and want to keep going. For our

kids, for our elders, for each other, and ourselves. We want it all to work, and it all can work, but

has anybody seen it? Who can see the whole thing, how it all works, how we all work, and communicate

that vision to everyone, gain everyone’s respect? How to bring everyone to the humble recognition

that we don’t know, but here is someone who does!?

Right now it seems we’re in the “we

don’t know, but no one does” stage.

OIOIOIOIOIOIOIOIOIOIOIOIOIOIOIOIOIOIOIOIOIOIOIOIOIOIOIOIOIOIOIO

Driving northward, through the cold- snow is coming, winter, real winter is in the air. We stop in

Pendleton, OR, tour the shop in front of the mill- they sell only yardage-find out that Royal

Stewart is made every 6 yr. or so, the tartans rotate through the years. The half- price clothing store

is in Washougal, WA, so we go there. I bought a nice red wool shirt that I still have. This has

been, and still is, part of the economy here- the woolen mill. They had a good rep with the Indians

around here on the Colombia river. The Indians traded designs for blankets. Entering this country

of the northwest is exciting still, the richness of it is still palpable: after most of the salmon have

been fished out, most of the giant swaths of forest cut down, the rivers dammed and the cities

built, and the place still feels rich in natural resources. The Indians here lived well on salmon,

warm in their wooden plank houses, well equipped with strong bows and arrows, spears, harpoons

and nearly indestructible canoes.

The dentillium shell. The real wealth of this region, as in every region, is the spiritual, the

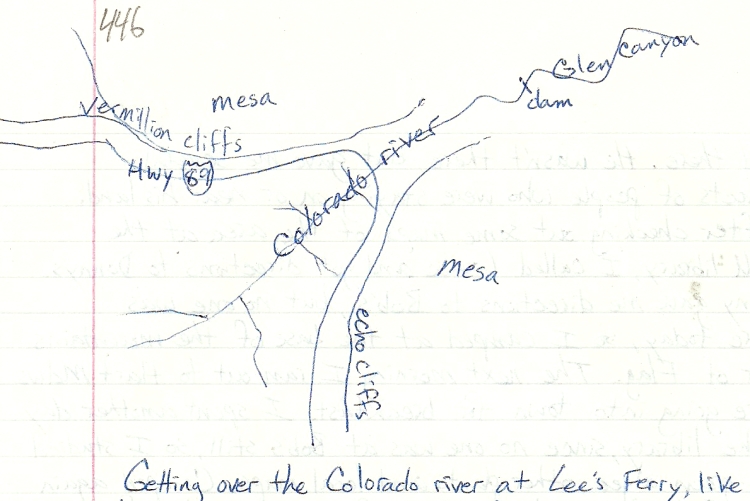

generous spiritual life which feed the organic life. Native people see the richness and abundant

giving of life itself. The inexhaustableness of the waves coming to shore, the reproductive powers

of animals on land and in sea. The Great Spirit is not exhausted, but constantly renews the

life of the land and sea. Native people want to be rich, rich like God is rich, inexhaustible, freely

giving, renewing and refreshing to the land and sea. It is humbling for a spiritual person to have

to eat solid food, to have to kill animals, process plants into food and fiber. To need trees cut

down for houses, for shelter against cold and rain and snow- this is humbling to a native person.

We want to be at least as strong and tough and happy as the animals who inhabit the land and sea,

rivers, and mountains. The Europeans saw something else. They saw an overabundance, more

food and resources than they held in their collective memories. They didn’t want to be as generous

as the Great Spirit; to eat and live in a house was not humbling to them. They wanted the

fruit, not to be like the tree. Not only did they want the fruit, but all the fruit- to hell with the tree.

The tree was incomprehensibly large, so vast and large it scared them, if there were less of it that

would be better, easier to manage and control. The words of the first settlers at Portland, OR (a

square acre of cleared forest on the confluence of the Willamete and Colombia Rivers) “the terrible

forest, so thick and dark, the awful numbers of trees, so thick they could never be cleared”. It

really was scary to them, this face of god.

We drove through the Yakima Valley apple orchards up over the pass into Seattle, WA.

We stayed for a week in the Capital Hill district, had Thanksgiving there. It’s hard to live in the

city, even for a week. The markets are fabulous, the food overflowing into the street; we ate royally.

The city surrounds you and doesn’t go away. The lack of open, green, natural spaces make

me withdraw, to the point where I had to create a myth; the city is built of natural materials, at

it’s base,. This helped a tiny bit, as did getting away to parks, the arboretum, and Widbey Is. But

the best solution to feeling better was leaving the city and heading back south, in the rain and

snow, after a week of clear, beautiful weather in the city. We took the Wilamette Valley south to

Portland, a more usable city, you can get out of it faster. “Powell’s World of Books”, the city

block, big, huge, bookstore was fun to sit in, reading, absorbing the creaky wood floors and big

doorways, high ceilings, leading to room after room of stories, facts, women, pictures, men, animals,

plants and wars. From Portland we went up and over the pass south of MT. Hood, a full

blast snowstorm had just hit the day before, we had gray rain in Portland, the standard weather

for that city, so the trip around Mt. Hood, in the dark, clear starry sky on snow packed roads, 30

mph. with chains on for hours, was quite memorable. Finally we made it to Madras, OR and

spent the night moteling. Next day to Bend, OR and in 5 min. had met Scott, the huge

German who was to help me so much. He was doing his bills, all spread out at a table at the Café

Paradiso. We spent 3 days in Bend, after which I told Scott we would be back to spend the winter.

Good Luck! We drove back to Bishop, unpacked, packed, cleaned up, Diane went to Denver for

Christmas and I, with truck and trailer in tow, headed north again for Bend, OR.

What am I doing, moving about the country? just because of a line on a map! NO! Yes! Why

not? Why?! People move because they have a job in a new place, relatives, a love interest, that’s

it a love interest, I have a love interest in the country, in the land, the mountain chains, the river

systems, the trail network, the sea coast, a love interest of the vast, trail-less, road-less desert.

And again- if it were just me with this idea, how far do you think I’d get? Not only does mechanics

stop you, finances can stop you, other love interests can distract you, and most of all, without

a very good reason, you will stop yourself, “There is no reason to keep going.” And while wild

abandon may carry you for several days, weeks or months, it will not carry you through season

after season, year after year, away from loved ones, away from people who need your company

as much as you need theirs.

So yes I have good reason, even when it is unknown to me, sometimes I know, and that’s

good enough for me. But to travel around the whole country, to visit 40 plus states, sail oceans

and walk mountains takes more than just good reason, sometimes. What can happen is that a person

can be moved around the country, which is a combination of the personal will to move (with

good reason) and the willingness to be moved by the breath of life, by the wind, as if on a sailboat; but even then it is a combination of the skill and will of the sailor and the will of the wind

and tide. There is a timing to follow, a time to go, a time to stop. Each day and each month, each

season and each year. A quick calculation back in 1995 told me that by ’99 or 2000 I might complete

one seven turned spiral around the country. Back in ’92 I had a vague idea that putting forth

on such a journey, I may finish sometime before 2000. This would be a beginning, with the possibility

of more journeys after this first, but to put forth on this one, to be in motion, this I called

“my life”, what was given me to do. Knowing that I was “skipping” certain parts of the country

by driving a car instead of walking is hard to accept, it’s hard to miss anything, to skip, to drive

right through a town and not stop, to drive around a mountain and not set foot on it.

But even by walking this would happen. I could be in one place, but not another. I would

miss events, human and nature, but this is the nature of individual existence- you can’t do it all,

see it all, be everywhere all the time. Some people give up, stay in place, realizing they are too

small and world too big to even try to pretend to keep up with all the events, with the surge and

flow of life. So they give up, content with the happen stance, the chance meeting or occasional

participation in ceremony and sweeping events. This makes their life seem “spontaneous”, because

they didn’t plan these chance meetings or sweeping events. There is nothing wrong with

planning and spontaneity is way over-rated. To know what is coming, to know where to be, at

what time, and follow through can be thoroughly thrilling. To know, to find out what each area of

the country, each city, each country holds as sacred, the special places are usually public, have

been known for years, if only by locals, and are usually accessible. When you know the places,

the events aren’t far behind, and they are continuous, just as places are. One side effect of modern

civilization is that it disrupts, interrupts, disconnects and separates places. Not only places

but events too. That equals space and time have been broken up. There is one place and one time,

and the event, the happening is continuous, so when you’re awake you are the happening place, not

missing anything at all. So why move, why travel? Well really you don’t have to, but there is

this possibility, this experience of seemingly moving about the country from place to place. But

the mind, the center, the love, doesn’t move, the recorder of events doesn’t move, everything else

does. There is breath, and changes, and the center, love. So to me, this movement is really not a big

deal, I’m grateful yes, but deserving of no accolades- that’s not why I’m doing it, not my rationale

or reason. The reason and practice is to follow my heart and leave my fears behind, face

them, yes, but keep going and not let fear stop me. Fear or anything that someone may say, like

“why are you doing that?”, “That doesn’t make any sense!” I really don’t need to answer questions

like that- I have only to do what I’m doing, and I know, at least for myself, that it’s not just

me doing it. I know that I’m being helped, guided, and that the success of completion is happening,

happening still.

Chapter TWO: West and Center

So in ’92 when I left a good job, family, friends, a beautiful, holy place to live, the questions

other people might have asked were a distant, secondary echo of my own, obvious questions.

But these questions were not and are not important: Questions like, “Why are you leaving

such a good thing?” The important questions are; “What good things are you headed for?” “Why

are you afraid to move?” “Do you trust what you say you believe in?” These questions were all

answered, in good time, but none of the answers were as important as those questions, for they

guide and urge life on- the answers are secondary. One can get bogged down in answers, or miss

them altogether, but a good question- that can keep you going for thousands of miles, years

worth of seasons, and it takes this measure and scope to see that for the vast questions of Ocean

and Sea, there is precious little river to answer. The Nile was an answer, the Tigris and Euphrates,

the Yellow, these are the great answers to the beginning of human civilization. The Mississippi,

Potomac, Columbia, Colorado, Rio Grande, Ohio, Missouri, Tennessee, James, Roanoke

PeeDee, and Delaware. These answers have all but been forgotten, some old history book, let

alone the question- what question? Was there ever any question? Any doubt that we would have

a Freddy Myer supermarket in the middle of the Oregon wilderness?

TTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTT

After two days of towing the trailer at 35 to 40 mph.- through snowstorms, slush and the

grand finale: the ice and snow covered, multi-rutted highway from Hell, highway 97 north from

La Pine to Bend. Just a 30 mi. stretch, but each time one of the semi-trucks passed me, and there

was a continuous stream of them, visibility was reduced to zero for about 5 seconds while the blizzard

of snow and slush flew off the back of their trailer into my windshield. I can talk about it

now, describe it and say that the tension was quite high for many hours, slowly bumping along,

my trailer lights flickering, growing steadily stronger as the vibration and friction continuously

cleaned and improved the electrical connections. Thoughts of having to chain up, spinning or

jackknifing on the ice, or some problem with the truck (the electrical system is a weak point),

were always there. The length of the trip, and the fact that I had no where to go when I got there, these

things were in my mind, but so were the antelope that ran down the road in front of me, barbed

wire fence on each side, keeping them trapped, dodging back and forth before my approaching

rig. As I slowed, they slowed, panicked a little, dodged back and forth some more, I

slowed more, riding their rumps before they were led to the fence on the left, squiggling under

the barb wire. I was aware of the animals, the deer and antelope living out in the desert, the desert

that was now covered with a foot or two of packed snow. I had it pretty good with my trailer

and food, blankets and propane heat. So when I arrived in Bend the big, half-empty parking lot at

Freddy Myer looked pretty good for a campsite. I stayed there 2 nights. Stepping out of the

trailer, a short walk across the parking lot and into the isles packed with bagels and cheese; this

was a different kind of life. The parking lot. Freddy Myer is a K-Mart, supermart, health food,

and discount auto parts store rolled into one, gigantic mall of a store. I got a gallon of Prestone

and a radiator fluid tester for 10 bucks. The parking lot was the size of most city blocks. My

truck and trailer could get lost in the confusion, the vast confusion of such a lot. There were kids

that played with their cars and trucks, spinning around on the ice in the parking lot. The all night

floodlights kept track of the main event this winter- the snow was falling. This winter the snow

fell continuously. At night you can’t see the white snow falling for all the blackness of a thickly

clouded winter sky, but shine a 10,000 candle power street light into the gloom and you can see

for about 10 feet, and that 10 feet is a moving, white speckled continuum, endlessly repeating

itself, beginning and ending in total blackness.

Each passing day the snow fell I felt more at peace, more sure that this was to be a real

winter, a good winter.

The next day my new friend Scott and I met late in the afternoon, and during the

day I called around town for housing and job prospects. The job hunt went from half-hearted to

completely fake over the course of the winter. I was still getting 400 plus dollars every 2 weeks

from unemployment insurance, as long as I didn’t do something rash, like get a job. Scott and I

met up at 5 p.m., and after a short visit he invited me to pull my trailer out to his land to stay until

I could find a place in town, which is what Diane and I wanted. We were both getting the unemployment

insurance, so we had a pretty good income at 1600 dollars a month, we were feeling

pretty well heeled. That night after dinner (Lebanese restaurant) with Scott and his friend Mark

(who lived in a tipi year round, this being his 5th or 6th winter, and the harshest), Scott and I hit

what was to be the social hang-out for the next four months- the public recreation center’s sauna

room. For 2 dollars and 50 cents you could sit for hours in pure, uninterrupted warmth. The outside

temperature rarely went above 32 degrees F. for the following months, so the sauna really

helped sustain our health and mental well being. A short haul that night out to Scott’s land; in the

morning we parked and leveled the trailer. After setting up the trailer we then pursued our formal

winter occupation- learning to ski.

There was skiable terrain in every direction- east, out into the desert on flat trails and seldom

skied cinder cones, north, more desert, south, more small mountains made of cinder cones

and now covered with a depth of snow, and then there was west, the Cascade range, dominated,

in our view, by the three sisters, especially South Sister, her majesty South Sister. We drove west

that day, the 19th of December 1992, up to Mt. Bachelor, a place I skied as an eighth grader, 26

years previous. We bought (each) a 33 dollars points pass and burned up half of it. Beautiful,

powder; creamy and soft packed powder, and deep, light virgin powder. I skied with a daypack

on, all winter, learning how to travel through the mountains covered with snow as well as having

fun. Just being in such a place as a snow buried forest, with the old volcanic peaks looking down

at us, just standing there, brought such a memory, such a fulfillment, such a feeling of destination,

this is it, the purpose and end. I stayed in my trailer out at Scott’s place east of Bend that

week while I looked daily for a place to rent. I started driving in to town, to the river park in the

center of town, praying there, offering and listening there each morning. On Christmas eve

morning I see a young otter swimming through the icy water with a fish in his mouth. That day I

secure a place to live for the winter with Dave and Jenny Sheldon, 600 dollars a month on the

river water front. Diane is still in California, coming up on the 8th of January. I move the trailer

over to the little guest cottage we’re renting and move in on the 4th of January. Until then I stay

at Scott’s, go skiing with him at Mt. Bachelor, Pine Mt. Observatory, down the river trail and

around the golf course. On December 29th I meet Darla, go to dinner with her and Scott

and McKensie’s. During this time I read the Trail of Tears book and took copious notes on it. On

the 31st I skied around the golf course with Darla, had dinner at the Mexican Rose and drove

home to my trailer. I stayed up past midnight talking with Darla, she told me how much of what I

talked about and said reminded her of her Gurdieff teachings. She couldn’t believe I’d never

heard of him.

This winter was very social and intimate and indoors even though Diane and Scott and I

exercised a lot, did a lot outdoors, but then retreated indoors to our homes, to restaurants, coffee

shops and bakeries. It was one cup of tea and loaf of freshly baked bread after the next. Everyone

seemed to crave each other’s company, always welcomed the guest and sought out the host for

the day. I looked for jobs nearly everyday, everywhere I went, which was all over town, exploring,

seeking, listening, discovering, and amazingly (to me) not one job offer. It was like I knew

that the best thing was to not work and the whole town was conspiring with me to keep the unemployment

checks coming and the ski opportunities constant. On January 22nd Mt Bachelor

had a ski for free day- what a concept, we accepted and did it all day. The next day we just had to

stay home and rest. Beadwork was at hand, I practiced by beading bottles. I thought of Mark often,

living in his tipi in the snow, with solar powered batteries providing light, and his wood

stove and heat. Scott had a yurt that he rented to Twig, who rode his bike to town for work in a

futon factory. Rhonda and Rob rented Scott’s cabin, so Scott lived in his tipi with solar powered

battery light and wood stove heat. Diane and I lived in the middle of city, in the old part, right

down by the river’s edge in our little cottage, surrounded by the right and wrong of the city’s

comforts and convenience; and too there was the river trail that led us out of Bend, right from

our doorstep we skied south and into the woods. The combination of money, cars, restaurants,

people in very nice clothes with the raw desert juniper/ pine tree covered foothills covered with

deep snow struck a sharp contrast between civilized man and pristine nature. The boundary was

hard to see sometimes, the expensive estate homes had spread quite a ways up into the forest,

and then you hit the country club. Oregon was undergoing Californication. Nature and Man were

layered un-uniformly into a thinner and thinner swirl as you approached the city center, and then

you hit Bond Park- the Deschutes river turns into Mirror Pond- the long grassy slopes of the

thinly treed city park slow dip into the Pond, stretching it’s long twisting length and crossing to

the other side to continue up into private back yards that have a public display aspect to them as

well. Marion, a long time friend of Laura’s, has just moved to this neighborhood in

Bend, neatly tying the end of this journey (where I began staying still), house sitting for Marion

while she moved to Bend from where I decided to stop, in Placitas, New Mexico.

The swans: then there are the swans in Mirror Pond, as if there had to be an aristocratic

touch to finish off this pristine city park, private estate contrast. The swans even, are natural, of

course, nobody brought them in, but here they are doing their mating rituals and breeding right

there in the middle of the river, in the middle of the park, in the middle of the city. Not unusual at

all, but at the same time, from a human stand point that has unintentionally gotten rid of such

natural proceedings by intentionally building buildings and uncontrollably more buildings

around a center of buildings that is ringed by and fueled by and has the purpose of expanding into

more and more rings upon rings of buildings like some fractal infinite message across the landscape-

that, then makes the swans being where they are amazing and wonderful and even more

non-chalant. They belong there, and everything around them, the park, the houses, the human

embellishment and paved pollution doesn’t belong there. I kind of feel like those swans sometimes,

belonging to the landscape, but in the present day context I stick out like a big signet on a

little city park pond. Who is out of place here? I have answered that question for myself and decided

that although I may look out of place, I don’t feel out of place, and certainly anywhere on

Earth that welcomes me with conveyance and air to breathe deserves my honoring that gift with

appreciation and upright self dignity. So I walk freely this city, these lands, trespassing not on

anyone’s private acre, but not afraid to stride through public places, to live and be comfortable

and alert to the possibilities of greater hospitality than I could ask for.

eeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeee

Doin’ the Bend thing- working out at the gym with Diane and the local smoke jumpers,

playing in the pool. Shopping for every little thing we needed, which included stocking up on

those necessities of winter life- cooking utensils, glove liners, hats, food, beads and more food.

The news President Clinton was inaugurated on the 20th of February, all hail the Chief!- so his

eight year are up this November, 2000, but anyway the Republicans were out and the liberals

were thrashing around, laughing out whenever they could-the forest was being shut down by the

spotted owl, mills were closing and the era of cut and run logging was coming to an

end.

We got out in the woods all right that winter, up to swampy lakes and broke trail all the

way back to Swede Cabin. We danced to Blueberry Jam with Peter Susman the musician and

skier. We watched the movie “Clear Cut”. The days were clear and cold. I looked for work, made

fry bread and spent money.

In February my unemployment benefits were extended another 6 months so I was set until

October. We rode our bikes around town and worked out, sauna, swam, eat, work, play hard,

rest, enjoy. The Britenbush hot springs were kind of nice, little pools we could rotate through, a

remnant of old growth forest nearby. We skied at Virginia Miesner Snow Park, all the way to the

cinder pit and back. I would ski Mt. Bachelor by day, and the same night be just as ready to do

the full moon ski to Tumalo Falls, that was the same night as Kelly Esterbrooke’s party- hence

the ski to the falls.

We bought fabric, sewed things, I worked on my leather shirt. We hung out with Rob and

Rhonda, spent time with Darla and Ashlen, and on my Birthday we went up to Simnasho on the

Warm Springs reservation to the Pow-Wow. Saw Nathan Jim, he was videotaping the dance. We

met Pricilla Bettles and found out Wanda M. went to jail. The dances were good, hearing the

three sisters pray was better, their singing and praying brought us all into the extended grace period

of reverence and love and for sure, they had been doing good for a long time. We went back

to Bend, it was cold, cold, cold, and snowing and I had to re-take my driver’s license test- had to

drive Kumquat through the snow drifts to pass for an Oregon license. Kumquat, the orange

Honda civic wagon, 70s era, chained up and barely warm enough to keep the windows defogged.

All this time in the city of Bend, with all the playing in the mountains, meeting people

and enjoying life, I knew it was just temporary, which was good, life is not easy or all that fun in

the city. The crowds of people, traffic, pollution and congestion. I was on a journey, knowing that

I would continue- but how or when or where, the details I didn’t know. Diane hears that Alpine

Hotshots are moving to Estes Park, CO and so she is going to apply there for a job. Her mom

lives in Denver, (her dad too) and so we start thinking about moving there. For me it seemed to

be a central location in the country- near the center, so I could rest, work, make money and save

for a trip around the country- but How that would happen I didn’t know- the distances were so

vast, so much land and changes of climate and people involved- it all seemed so impossible, but

this was hopeful- the move to the center, to Colorado to gain some understanding of the whole.

RRRRRRRRRRRRRRRRRRRRRRRRRRRRRRRRRRRRRRRRRRRRRRRRR

We stocked up- I bought a stockpot, a new skill battery charger and many parts and

pieces for the truck and trailer. I went to the high Desert museum, saw porcupines and otters. The

otters were so happy and content playing and sleeping with each other. They had a stream and a

den and food and each other.

I spent time making a bivy sack and putting a headliner in the truck; going out to friends

houses for dinner often. Diane and I went out to the “knapp-in” at Glass Buttes, camped out and

visited with all the flintknappers there. There was a young man there whose work was fantastic – very

fine, large blades. He also made extremely small points- very good skill. I met Steve Alley,

an imitator from Sisters- he reproduced Indian material culture for museums.

I went up to the Warm Springs museum with Rhonda- they had a good history story with

lots of pictures and were experimenting with audio/visual equipment to document their recent history.

Skiing and eating were still the big activities in March, and toward the end of the month Diane

left for California to visit Miriam, then traveled on to Denver to se her mom and to start getting

ready for work in May. I worked on the redwood tables from Sequoia, and the oak ones too,

while still putting in an effort to look for jobs. Writing letters still to Pat, Nicholas, Diane and

Margo. Scott and I dug willows and planted them at his pond. I’m having trouble getting the

truck tuned up- finally figure out that all points are not created equally- the good ones are at the

Chevy dealer. Scott and I skied some more- one day he lost a ski and it turned out that the binding

just broke right off- well I had a good laugh, but he had to walk all the way down the mountain.

It’s April and the snow is getting heavy. I bruised my knee on one run at Mt. Bachelor, and even

Tuamlo Mt. Wasn’t holding the light powder any more. I knew my time in Oregon was growing

short- at the end of April I planned on hauling the trailer to Colorado, to Estes Park, to live with

Diane there. This month of April was full, with skiing every chance, going to a juggling convention

in Portland with Darla and Ashlen, and I even had time to go up to Warm Springs reservation

again and get my truck stuck in the mud. Eight hours of digging and building ramps with

rocks and I was out- not a problem, but I did miss the mini-marathon (that was the reason for going

up there). Caught some good music and had many good dinners with friends. I met Lezeazl,

Pepe and Stacy, we danced to Ed and the Boats at Cafe News. April turned to May and everyone

was running at full speed- they knew I was leaving soon, so things became stressed, separation

anxiety. By the 3rd of May I was packed up and ready to leave for Colorado.

Chapter Three: Holding the Center

A farewell breakfast

with Rhonda and Scott and Andrew and I then launched out of Bend eastward to Burns, then Crane, Oregon for

lunch near the hot springs. The Owyhee river- Rome, the only town for many miles along the

river- this was my camp for the night. This river is amazing- most of it runs through wide open

high desert in northern Nevada and Southeast Oregon, but it runs in a deep canyon most of the

way- so not only is the surrounding country isolated from population and access, but then the

river itself is almost inaccessible, sheer cliffs and maybe one road leading out to the south- no

services no towns, maybe a ranch house, but very few of those. Leslie Gulch. Very remote. I met

two river guides, Dave and Jake. We visited, talked about raft trips, then Dave points out my

broken shock on the truck. The road from Bend to Burns was long, straight and every so often,

a huge pothole, more like a crater, that took out a whole lane of the two lane highway, loomed in

front of me- I would hit the brakes, try to swerve (towing the trailer) and then ca- chunk! Hit the

crater head-on, bouncing through and looking back to see if the trailer was still attached. Lucky

to only break a shock. In Jordan Valley I had it welded back on for 15 dollars. I had a

good visit in Rome though. Saw antelope, went running, a pack of coyotes came near at

dawn. I picked wormweed and talked with the river.

**************************************************

Another special trip in April was out to the

Alvord Desert by myself, in the big green truck. The first night I camped with no else around at

Glass Butte, where the knapp-in had been the month before. Now the ground was very muddy

and soft, except at night and early morning when it was frozen solid. Glass Butte has good obsidian,

large boulders and piles on the surface, but I didn’t dig any. The next day I went to Burns,

hung out, read the paper, then went south down to Frenchglen. Going through the extensive

Malhuer Wildlife refuge, where the only high spot was the road, the vast expanse of wetlands

going for miles and miles, it was all rather dry and barren for such a wet year. Maybe it

was early yet and the water had not flowed in, but he region is so dry and windy, and water may

have been diverted or other uses. Frenchglen is a weird little artsy cowboy place- advertising lots

of local happenings. I went up the Steens Mt. Loop rd. for 10 miles. Until the road was closed

and camped. In the morning I had a nice run for another 3 miles on the closed road. The mountain

has a huge snowfield on top- good for a day’s worth of skiing for a person who would climb

to the top. The weather moves in fast, the creek’s name is a clue to the routine here- Donner and

Blitzen (Thunder and Lighting). I move down the road, lower in elevation and to the east side of

the mountain to Fields, but the weather is big and driving rains is all around up to the Alvord Desert.

I camp at Frogspring, wait and watch the weather, what a show- watching lake reflections

all afternoon. The weather breaks a little and I hike up toward the mountain. A large deer herd of

30 or so sees me and moves ahead- far up the side of the alluvial fan to watch me. I return to have

dinner and write Diane. In the night I wake up scared, feeling a strange fear- couldn’t shake it, so

I actually get up and open the back of the camper, stand up on the tailgate- pray to the night air,

the sky and the shoosh right over my head; an owl swoops by, just missing my head, but the fear,

it’s gone, like he took it- that owl helped me, but I had to stand out there and face that blackness,

that weird fear. The next morning is glorious, running up the road to Alvord Hot Springs. The dry

lake bed is now full of water! Water an inch deep and miles across. I can’t even focus on the horizon-

it appears and disappears, it all looks so unreal- like a movie set. There is no reference

point. Standing on the shore looking at the water- I can’t tell if the water is 10 yards away or a

100 yards away. There is literally no reference point, not a stick, let alone a tree; not a rock, nor a

print in the sand- just smooth, hard packed dirt, then the edge of the water- no grass, no vegetation

at all. The longer I looked the less I could tell about what I was seeing; then the wind started

to make ripples across the water- it actually moved the water around so that land would appear,

the edge was now totally undefined; the water was still coming down off the mountain from the

previous day’s rainstorm. This was still filling the lake. Then the wind and sun of today were

evaporating and moving that inch of standing water around on the lake bed like snow blowing

across a frozen lake. I couldn’t tell if the lake was filling or receding- it was doing both at the

same time and I could see it happening. I couldn’t tell how far across the lake was. I found out

later it was about 5 miles. It could have been one mile or ten or twenty- I had no idea, no reference

again, only a little set of hills just stuck on a short piece of the horizon. At 3 p.m. I headed

back to Bend.

**************************************************

These little trips of just a couple days proved to be the times that were heavy with memories

and deep experiences. The trip to Colorado was planned for the most direct and the least

amount of mountain climbing with the truck and trailer. Having the trailer along was nice for

camping and stopping along the way. The time had come to move again- crossing the country as

I’d not done before- a northern route from Oregon to Colorado via Idaho, Utah and Wyoming.

After running the gauntlet of potholes in eastern Oregon and getting the shock fixed in Jordan

Valley, I was on my way to the Snake River and southern Idaho. The border of Oregon and Idaho

was memorable for the hillsides covered with mules ears (Wyethia) I stopped and walked among

them, observing them carefully.

The border, and I’m starting to notice the borders as pathways, the

good places that are forgotten in between here and there. The no-man’s land conveniently left

behind as “borders”. The seams that are easy to follow. Nampa, a weird town of conservative

farmers, lots of hidden money, power, influence, but deserted, forgotten, and left alone alike so

many small towns that aspired to be big- and maybe they did, but there are only so many bigs, so

many places that not only had the people, but the culture to give an atmosphere, a center to the

mass of people. Boise is the one big in Idaho, and that is just out of sheer isolation of wealth that

Boise is still there- kind of a sub-station, a convenience for other cities- a stop between Salt Lake

and Seattle. And so I hit I-90 to cross that great expanse of southern Idaho- “snake river plateau”.

I took in that whole stretch from Nampa to Twin Falls and then pushed on to Sublett, I.D. for the

night. Good ‘ol Sublett, Idaho. A truck stop there, thriving along like those popular ones do. I

asked them If I could park my trailer for the night just down the dirt road to the north of the truck

stop. I had an unmemorable dinner, and dessert there, called Diane on the telephone to let her

know I was still coming along, then went to sleep in the nice trailer all cozy and warm on that

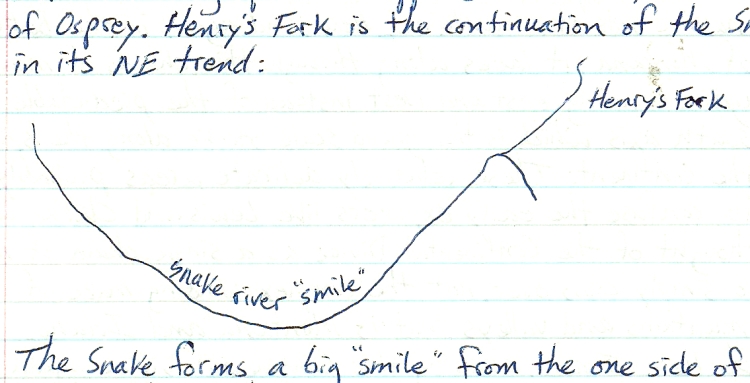

still chilly May 5th.